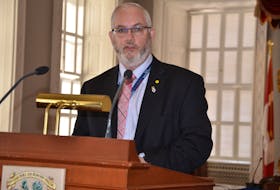

Bruno Gaudet takes the steps at Cheticamp Boat Builders three at a time.

“I’m telling everyone I’m not committing to any more deadlines and hold onto your boat,” said the yard’s 58-year-old owner.

Cheticamp Boat Builders is booked with refits and new builds for the next four years.

Inside its big steel building on Wednesday were two fibreglass Cape Islanders under construction and outside a new diesel engine was getting lowered into one getting repowered at the pier.

Since he started with two uncles and his grandfather building wooden boats at the yard in 1979, Gaudet has never seen it this busy.

“I’d like to find a way to work less to be honest,” he said.

But that’s not going to happen any time soon.

The southern Gulf of St. Lawrence crab quota went up 32 per cent to 32,480 tonnes this year.

Between the offshore and inshore quotas about a sixth of that will come over the wharf in this Acadian community of 3,000 souls this summer.

At $5.50 a pound that’s $60 million worth of snow crab.

Then there’s lobster and other less valuable fisheries.

This week it’s the offshore quota coming over the wharf.

On Friday, there were 30 boats from around the Gulf of St. Lawrence coming and going from Cheticamp Harbour. That’s on top of the 40 local vessels, most of which will be catching inshore quotas in July after lobster season ends.

“So far so good,” said Pierre LeBlanc, general manager of Cheticamp Fisheries.

His plant employs 140 people processing crab from season’s opening in early May until mid-August.

Ninety per cent of it will head south to the United States with the rest going to Japan.

But it’s not just fishing boats that come to the Gulf chasing food.

In 2017, 12 endangered right whales were killed — necropsies showed seven likely died after being hit by boats and two from fishing gear entanglement.

The whales have been coming to gorge on fatty little creatures called copepods.

While historically the annual migration from southern winter breeding grounds saw most right whales feeding in the Bay of Fundy, lower production in that body of water over recent years appears to be making the mammals travel further north.

Fisheries and Oceans Canada estimate 190 of the 411 remaining members of the species were in the Gulf of St. Lawrence feeding last year.

The 2017 deaths cost the southern Gulf of St. Lawrence crab fishery its coveted Marine Stewardship Council certification as a sustainable fishery.

Strict measures put in place for last year’s crab fishery included limiting vessel speed to 10 knots (or 18 km/h), a large area completely closed to fishing where 90 per cent of right whale sightings had occurred and temporary 15-day closures of areas around where any right whales were spotted from regular aerial surveys.

“It’s hard to tell if the management measures were responsible for there being no mortalities last year,” said Jean Francois Gosselin, a biologist with Fisheries and Oceans Canada.

“Maybe it was part luck, part good measures.”

Meanwhile trials continue on fishing gear that sees boats remotely triggering a trap to release their buoy from the bottom as the vessel approaches.

The Marine Stewardship Council declined to lift the suspension of its certification for the 2019 season.

“Despite the management measures implemented in 2018, the certifier determined that known direct effects of the fishery, defined as entanglements with the potential to result in mortality of individual whales, are likely to hinder recovery of the (North Atlantic right whale) population,” reads a statement issued by the council in April.

The other major stress on the fishery is typical of all rural resource industries — high capitalization.

While those who pioneered the fishery a few decades ago were issued licenses, new entrants have to buy their licenses from other fishermen. Inshore licenses are sold by the trap in private deals but the going price appears to be $130,000 per trap.

The price is reflective of the fact that fishing three crab traps for two weeks can result in as much landed value as fishing 250 lobster traps for two months in the Gulf of St. Lawrence.

“No,” said Gaudet when asked if the boom would continue.

“No industry can stay on top forever. I hope it does, but it can’t. I’ve seen three down-turns in my time. But if fishermen run their enterprises like a business they can survive the lean years.”