It would be too easy to blame Queen Victoria.

And certainly the aging monarch played her part.

But she couldn’t have known the end result of sending a European beech sapling to Halifax in 1897 to celebrate her halfcentury on the throne would end in the near elimination of this province’s most plentiful hardwood.

Because that little sapling planted dutifully by her subjects in Halifax’s Public Gardens had a little critter in it — a sapsucking insect the size of an aphid that punctures a little hole in the bark where it lays its eggs.

Alone, the insect would have been a minor nuisance, but the little holes it pricked with its stylus were the perfect entrance point into beech’s thin bark for a fungus.

Though the queen’s European beech was immune, our American beech weren’t. Within five years American beech trees around Halifax were dying.

It was a big deal because surveys from the time show American beech, living up to 200 years and with lumber as hard as sugar maple, accounted for 60 per cent of this province’s hardwoods.

The insect and fungus, happy friends they were, swept like firethrough Atlantic Canada and down into the northeastern states.

By the 1940s the beech was all but gone — given the nickname “snap beech” for the way the standing dead trees broke in the wind.

So fell one of the lords of the Acadian Forest.

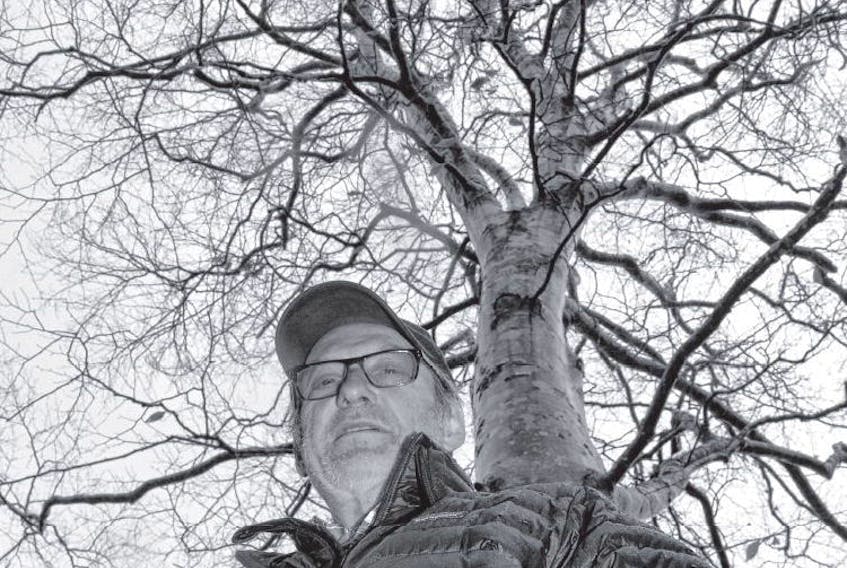

But hope, even if just the smallest glimmer of it, remains. Because on Saturday morning Henri Steeghs was standing under

a towering, healthy American beech in Monastery, Antigonish County.

“It’s such a beautiful tree it defies description,” said the Antigonish County tree enthusiast and former owner of Pleasant Valley Nurseries.

All around were its gnarled and stunted fellows.

Steeghs has spent the past decade seeking the disease-resistant American beech.

If the American beech is to survive then these individual trees hold the genetic key.

“I tend to be drawn to these projects with limited chance of success,” said Steeghs.

Steegh’s idea is to give nature a little nudge so perhaps his greatgreat- great-great-grandchildren might live to know forests where the American beech has retaken its throne.

In 2011, Steeghs and his longtime co-conspirator in all things plant-related, Bruce Partridge, drove to Fredericton to see what was left of the research conducted into beech bark disease by a program that had its federal funding cut under former prime minister Stephen Harper.

They’d created the saplings by grafting cuttings from resistant trees to rootstock.

“I thought, piece of cake,” said Steeghs, who had done thousands of grafts of all manner of tree species since opening a nursery in 1973.

Wrong.

Problem 1 — Beech is so hard you can’t cut it smoothly with a grafting knife.

Problem 2 — To encourage healing you need to apply heat and mist to the graft

union while keeping the wood above andbelow cool.

Problem 3 — The new growth needed for grafts is found upwards of 10 metres off the ground in a healthy beech.

Problem 4 — Beech cuttings must be taken in February and must be grafted very soon after being cut.

Problem 5 — Even if you religiously follow the dictates of rules one through four, most of your grafts will fail anyway.

Steeghs spent the next winter stomping all over Egg Mountain, near the Antigonish/Pictou county line, and following up on sightings of healthy beeches that came his way across northern Nova Scotia.

“When you find a single healthy tree it’s very difficult to say if it’s resistant. It could be near a coastline where the prevailing winds during the time of dispersal are on shore, so it is protected by geography but not genetics,” said Steeghs.

“So what you’re looking for are these beautiful, huge trees that are surrounded by diseased trees. Because they must be resistant.”

In the Februarys of 2013 and 2014, Steeghs returned to his big, beautiful beeches, lugging the tallest ladder he could find through the woods.

With his loot of new growth he rushed home to begin the painstaking process of grafting them to rootstocks.

He now has 25 resistant saplings cloned from four different trees.

“My efforts working alone at this are pitiful. This needs to be handed over to a small team with a good facility,” said Steeghs.

The goal would be to create an orchard of clones from about 40 resistant trees and plant them far enough away from any diseased beeches that they would be genetically isolated. By pollinating each other they could create a strain of genetically resistant beech that would, over a thousand or more years, march back and reclaim the land they have lost to ancient competitors like the red maple.

It’s a long shot to reclaim the accidental damage of an aging Queen.

And one Steeghs would never live to know the results of.