Families can have a defining narrative — one story that, with its power, seems to overwhelm all others.

The story that would forever mark the Korn family, who eventually found their way to Halifax, had its beginning about this time of year, around the High Holy Days of 1942, with the butchery of the Nazis’ Final Solution already well underway.

When David Korn was five and his brother six, their fearful parents put them into hiding, first with a farmer in a neighbouring Slovakian village, then with an aunt and uncle.

Finally, they found shelter in a Christian orphanage, which also hid dozens of other Jewish children.

For three years the Korn brothers waited there for their parents to return.

But their grandmother died in the gas chambers of Auschwitz. So did their parents.

Pain, the way David has told the story, followed him and his brother as they moved to orphanages in France and eventually Israel.

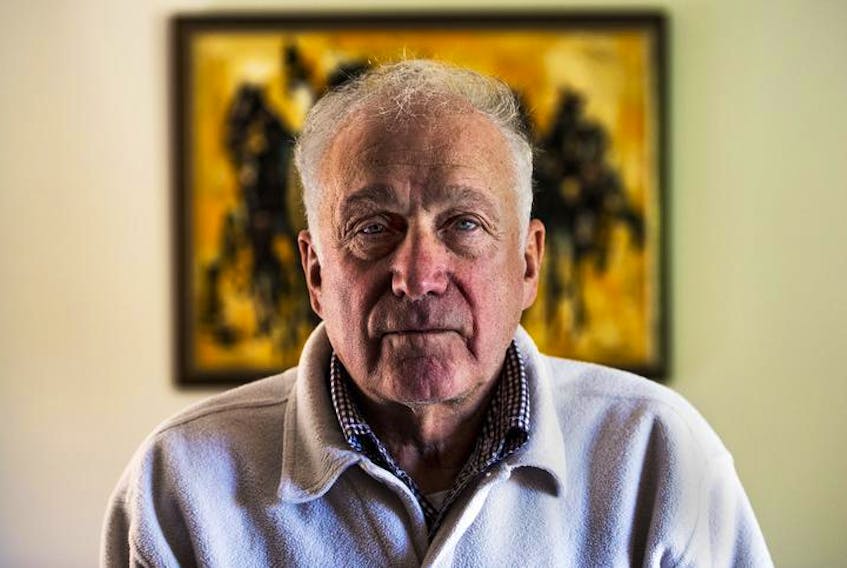

In time David came to Canada, meeting his wife in Montreal, before settling in Halifax in the early 70s where he began his engineering career.

He is 82 now but vigorous enough to go for regular swims in Halifax’s Chocolate Lake this summer.

On Tuesday night Korn was scheduled to sing a solo in Kol Nidre, the prayer at the opening of the Day of Atonment service on the eve of Yom Kippur

“My father has always been very positive,” says his daughter Miriam. “He thinks of himself as lucky to survive, rather than unlucky at losing his parents .”

David’s story is never far from the thoughts of his daughter, a Harvard-educated psychiatrist.

How, for any offspring of a Holocaust survivor, could it not be?

As a child Miriam, who is 49 now, heard all of the terrible stories about the Holocaust and suffered regular horrific nightmares about what her predecessors endured.

Later, as her son grew to the same age her dad was when he went into hiding, she grew anxious about her boy’s safety.

“I assumed that a lot of mothers became anxious when their sons hit that age,” she said over the phone recently from Victoria where she now lives.

That was around the time that a 2015 study appeared that got her thinking that maybe her anxiety was due to something deeper.

By then the children of Europe’s Holocaust survivors have been widely studied by scientists.

Three years ago, a research team at New York’s Mount Sinai Hospital, led by Rachel Yehuda, considered the genetic makeup of 32 Jewish men and women who had either been interned in a Nazi concentration camp, witnessed, or experienced torture or who had to go into hiding like the Korn brothers.

They also analyzed the genes of their children and grand children.

What they discovered was that children born to holocaust survivors who suffered post-traumatic distress disorder were more likely to develop PTSD, depression, anxiety or some other disorder than the offspring of Jewish families living outside of Europe during the Second World War.

The conclusion: “The gene changes in the children could only be attributed to Holocaust exposure in the parents,” as Yehuda said in an interview.

What Yehuda was talking about is something known as “epigenetic inheritance”, the notion that when someone suffers a trauma, the impact may be so shattering that it clings to the familial DNA.

In this way the ghosts of the past, as one writer has called them, are passed down from generation to generation.

The idea of epigenetic inheritance is a controversial one in the scientific world. Some experts in the field have reservations about Yehuda’s data and conclusions.

They say, among other things, that it is impossible to separate the influence of genetic modification from that of the horrific stories the descendants of holocaust victims heard, and the films and pictures they saw, as children.

Korn, the psychiatrist, thinks the science around epigenetic inheritance is still too young, and that there needs to be a lot more study done before it is possible “to tease out what is genetically inherited and what is absorbed as a child.”

Yet idea that trauma travels through the ages is nothing new. The cross-generational toll on the children of African slaves have been studied. So have descendants of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, the genocide in Rwanda and the 9/11 attacks in New York.

Amy Bombay, an assistant professor at Dalhousie University’s Department of Psychiatry and the School of Nursing has been studying the role that epigenetics play in passing along the trauma suffered by Canadian residential school survivors by their children and grand-children.

The list is legion: the offspring of residential school survivors, she and her team discovered, are more likely to consider or attempt suicide, to suffer from substance abuse problems and even to find themselves in foster care.

“Our research shows that when a large proportion of a group has been affected there can be a lot of impacts in future generations,” she says.

What she means is that, in the most basic way, the parallels between the children of the holocaust and the offspring of residential school survivors are undeniable.

Some evil can never be forgotten. Some wounds, those that transcend generations, never heal.