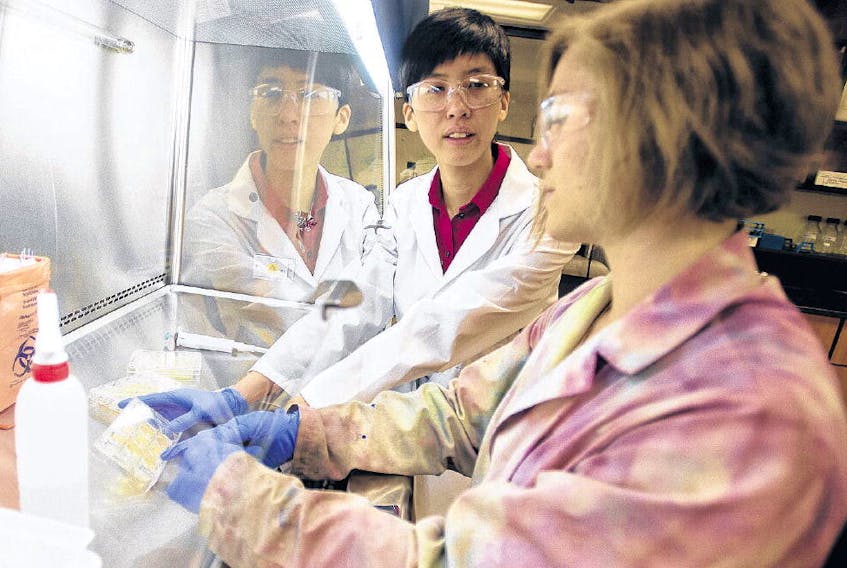

Clarissa Sit dedicates her workday to finding new ways to battle infections that have become resistant to existing antibiotics.

The importance of this work took a tragic turn into the chemist’s personal life last year with the death of her younger brother.

Matthew, 24, developed Clostridium difficile while in hospital shortly before he died, Sit recounted in an interview at her lab at Saint Mary’s University in Halifax.

As a person with special needs, Matthew dealt with many medical issues, so he was particularly susceptible to that virulent intestinal infection, she said.

The doctors tried several types of antibiotics until finally Matthew was put on Vancomycin, “which is what we call the drug of last resort,” Sit said. “By the time things sorted themselves out, he was suffering from major inflammation.”

The decreasing effectiveness of these kinds of antimicrobial drugs has led to a spike in deaths related to bacterial infections. According to the Canadian Patient Safety Institute, about 220,000 Canadians develop infections such as C. difficile and MRSA (methicillin- resistant staphylococcus aureus) each year resulting in at least 8,000 deaths.

The problem can be traced to the overuse of antibiotics and the ability of bacteria to find ways to survive their attack, Sit said.

Compounding the problem, the pharmaceutical industry doesn’t put much effort into developing new antibiotics these days because it’s not much of a moneymaker.

“Their rationale is it’s better we find things that treat heart disease, something that somebody has to take every day for the rest of their lives, then that’s guaranteed income,” Sit said, as opposed to an antibiotic that only has to be taken for 10 days.

As a chemist with a background in microbiology, Sit is attacking the superbug problem by studying

the chemical reactions that result from pitting two types of bacteria against each other.

“We’ll take two completely pure strains and then force them to grow in the same space,” said Sit, who was awarded a $171,000 grant last year from the federal government’s Canada Foundation for Innovation’s John R. Evans Leaders Fund. “They generally don’t like that. They’ll produce molecules, chemicals, that are designed to send the competitor off. . . . Once we figure out what those are, we want to evaluate, can those be useful antibiotics or some sort of drug to treat infections and things like that?”

LOWER RATES IN REGION

While deadly outbreaks do occur in Atlantic Canada, such as the 11 C. difficile-related deaths at Cape Breton hospitals in 2011 — superbug rates in hospitals are lower in this region compared to central and western Canada. For example, in 2015, there were 2.91 cases of C. difficile per 1,000 patient admissions in 2015 in Atlantic Canada, compared to 3.43 in Ontario and Quebec and 3.45 in western provinces.

“We’ve been fortunate in the rates of resistance, historically, we’ve had less resistance here compared to other centres,” said Dr. Paul Bonnar, an infectious disease physician in Halifax.

It’s not known exactly why that’s the case, although Bonnar said our relatively small population and lower immigration rates might be at play.

“But all of that is changing,

certainly as populations grow and more invasive procedures, more antibiotic use, more travel internationally and immigration all adds to a change in the resistance patterns,” said Bonnar, who is co-lead of the Nova Scotia Health Authority’s Antimicrobial Stewardship program.The stewardship program was established last year to monitor the number of antibiotic prescriptions in the province, with an eye to reducing the antibiotic overuse that allows bacteria to become drug-resistant.

“The more effective interventions are reviewing antimicrobials and given some feedback to prescribers on how they can optimize their antibiotic use,” Bonnar said. “That takes up most of our time . . . . People have been very receptive to that feedback. Everybody wants to do what’s best for their patients and if we can help them optimize their antibiotic use, that’s going to improve patient outcomes.”

PATIENTS GROUP CALLS FOR MORE ACTION

A national patient advocacy group said more must be done given the impact of drug-resistant infections.

“I would say from a patient’s perspective, we can always do more,” said Anne MacLaurin, the patient safety improvement lead for the Canadian Patient Safety Institute, said from the CPSI’s offices in Edmonton. “It’s very traumatic to the patient, detrimental and we could always do more and do better.”

For example, there should be a consistent standard across the country for how we measure infection rates.

“There’s not one single thing,” MacLaurin said.“Leadership making it a priority, good measurement surveillance systems in place, resources right at the facility level.

From an individual health-care provider, things like good hand hygiene practices would be things you’d be looking at.”

Concerns have long been raised across Canada, including Atlantic Canada, that hospital staff don’t wash their hands when they should.

A monitoring project in Cape Breton in 2012 revealed that hand-washing rates among hospital staff reached up to 100 per cent when staff knew they were being watched; the rate dropped to 60 per cent during undisclosed surveillance, with the worst offenders

being doctors. New Brunswick auditor general Kim MacPherson uncovered a similar problem in that province in 2015.

But Bonnar said he believes handwashing rates are improving in hospitals.

“As a recent graduate, it’s a heavy focus of my training and the medical schools,” he said. “It does speak to the difficulty of changing behaviour so just changing the routine of health-care workers.”

Back at Saint Mary’s, Clarissa Sit said it’s critical that government, academic institutions and private interests such as the pharmaceutical industry put more resources tackling the problem of drug-resistant disease.

Since losing her brother last year, Sit’s passion for the work burns brighter than ever.

“Watching him go through that process definitely reaffirms that I’m doing the right line of work for me. Now I have the extra motivation because it’s like, he’s got to have a legacy and his legacy is how he touched other lives.”