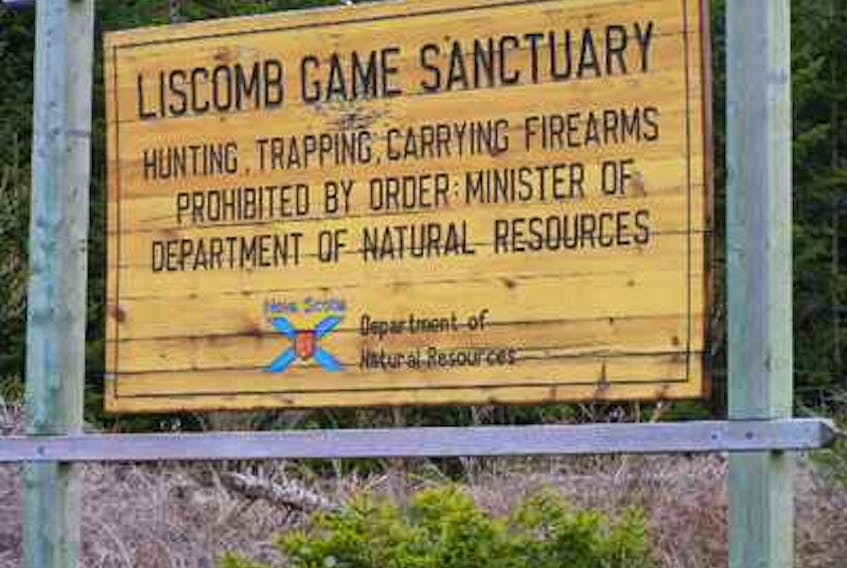

A large wooden sign at the entrance to the Liscombe Game Sanctuary warns that hunting and trapping are forbidden.

Clearcutting, quarrying and gold exploration, however, are fine.

And all three are happening in the Liscombe Game Sanctuary with the Crown’s blessing.

Atlantic Gold, which operates an open pit mine in Moose River, is exploring within the sanctuary boundaries.

A quarter of the Liscombe Game Sanctuary’s 42,311 hectares is privately owned — most of that by Northern Timber Nova Scotia.

The Registry of Joint Stocks lists that company’s directors as former premier and chair of Northern Pulp’s board of directors John Hamm, mill manager Bruce Chapman, Halifax attorney John Roberts, and Choong Wei Tan.

Northern Timber purchased 475,000 hectares of land from the Pictou County pulp mill’s former owners, including portions within the game sanctuary, in 2010, courtesy of a $75-million

loan from the province.

Large areas of the sanctuary have been cut.

Randy Milton, manager of ecosystems and habitats for the Department of Natural Resources, said the “game sanctuary” designation protects animals from hunting or trapping, but not their habitat.

“It’s an old designation that still exists on the books,” said Milton.

In 2004-05 the province held public consultations on delisting game sanctuaries based upon reports from government biologists that they were not fulfilling the purpose for which they were intended. The idea behind their creation was that they would become breeding grounds from which wildlife populations would expand.

Declining moose, caribou and beaver populations were the biggest impetus for the large Liscombe, Tobeatic and Waverley game sanctuaries during the 1920s.

“Conditions in the sanctuaries are such as to fully warrant their existence, and it is felt that they areserving a very useful purpose in the protectionand conservation of game and supplying a considerable surplus to the surrounding territory,” reads the province’s 1935 Lands and Forests annual report. “It is hoped by the department that more of these sanctuaries will be established in

the future . . .”

A year later, the province bought 20,000 acres of burnt woodland and dubbed it the Chignecto Game Sanctuary.

But a few things happened after that — beaver populations recovered (largely), woodland caribou went extinct in Nova Scotia and it was discovered that moose were being killed by a nematode that cared little for the borders of game sanctuaries.

While the designation persisted, harvesting to feed the growing pulp and paper sector through the ’60s and ’70s intruded into the sanctuaries.

“What’s happened with the game sanctuaries is the same thing that has happened with industrial and Crown land throughout the province,” said Wade Prest, a longtime forester and advocate for sustainable harvesting in Mooseland.

When the province moved to delist them in 2004-05, however, there was a public outcry.

That outcry brought new attention to the sanctuaries.

“To our surprise we learned that game sanctuaries protect the animals but not the habitat,” said Vicki Daley, a member of the Cumberland Wilderness society.

“Our feeling was, how can you protect the animals without the habitat?”

Cumberland Wilderness began a campaign to protect the Chignecto Game Sanctuary from harvesting.

Their campaign coincided with a commitment by Darrell Dexter’s NDP government to protect 13 per cent of this province from development under a new designation — wilderness area.

Most of the Chignecto Game Sanctuary falls within the Kelley River and Raven Head wilderness areas. While the province has met that commitment, only 833 hectares of the Liscombe Game Sanctuary’s 42,311 hectares is covered by wilderness areas.